Councils of local governments elected last year will form the electoral body which elects Estonia’s next president.

Councils of local governments elected last year will form the electoral body which elects Estonia’s next president.

With two long years remaining till presidential elections, a potential first round was held at the local elections, last fall. These very elections will, among other things, determine who and how will make it into the electoral body to choose the next president.

At the moment, the discussion is surely theoretical as the president might get elected at Riigikogu. For that to happen, the candidate must get 68 votes i.e. 2/3 of Riigikogu.

Thus, for instance, Toomas Hendrik Ilves did get 75 yes-votes, the last time, and proved elected. Mr Ilves’ initial term, however, was launched at electoral body where he got 174 votes – the threshold being 173. So, the win was narrow.

Also through electoral body, Arnold Rüütel rose to be President in 2011, getting 186 votes against 155 by Toomas Savi. Lennart Meri got elected for second term at electoral body, pocketing 196 votes against 126 by Arnold Rüütel.

Measuring party power

Looking at present party support or results in real electoral situations (these same local elections, in October) and understanding the Estonian electoral system, it may quite confidently be said that a situation where two parties would secure 2/3 support at presidential elections at Riigikogu is highly improbable. Thus, in order to elect a president – no matter if nominated by a left of right wing party – cross-coalition support would be needed at Riigikogu. Should this not be achieved, electoral body will take over.

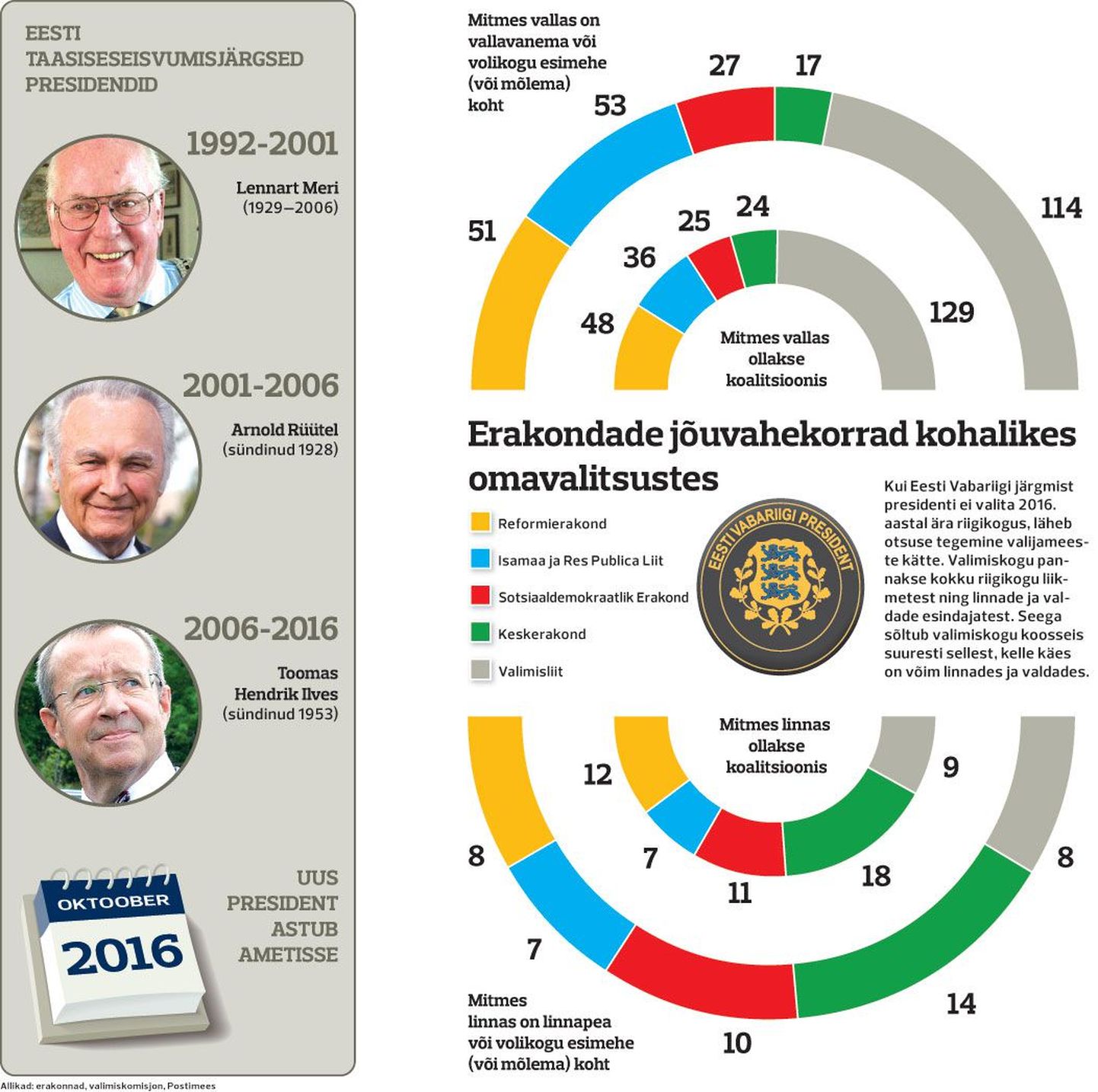

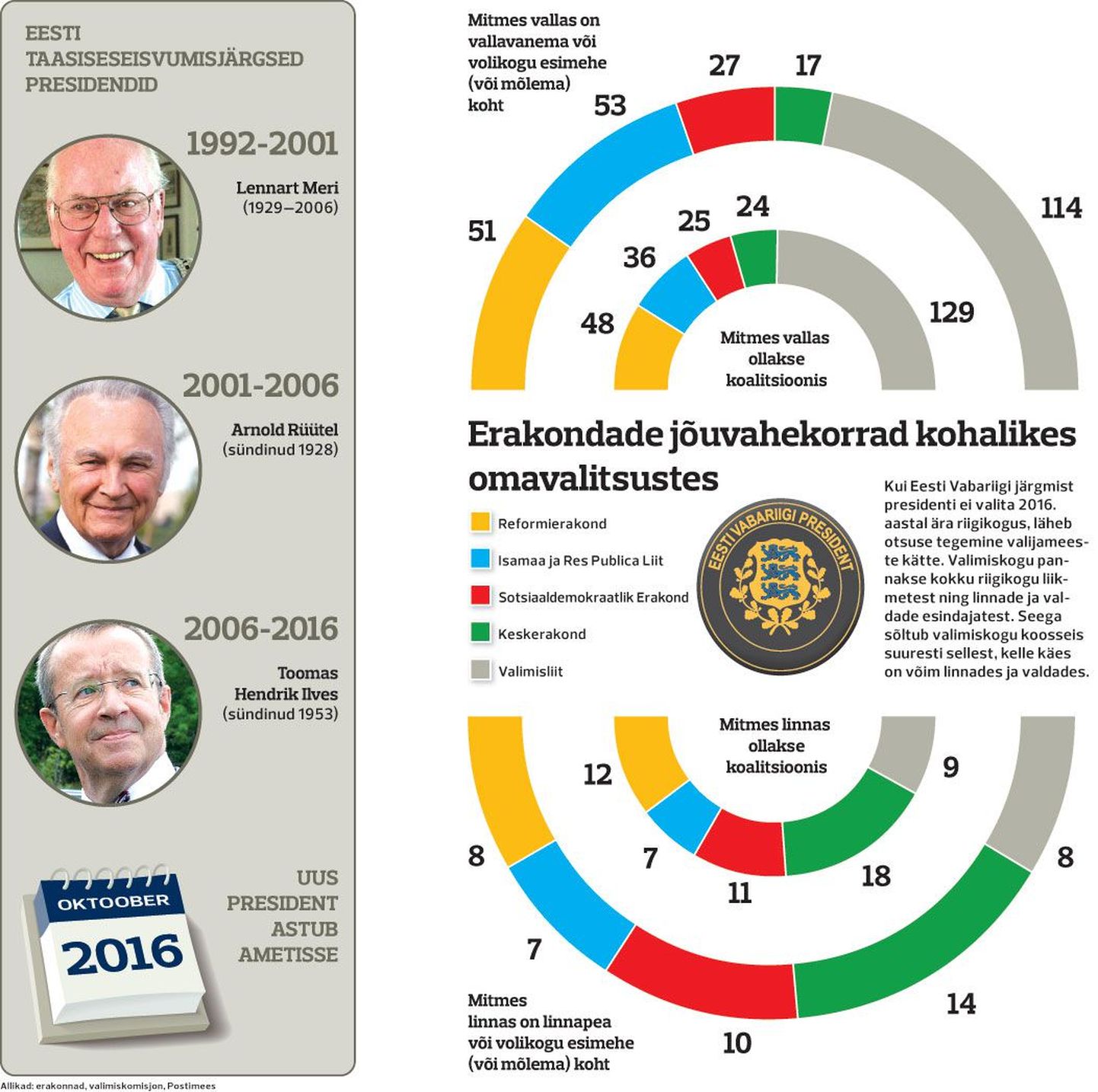

Postimees collected data of all Estonian communes and cities in order to see which parties and election coalitions succeeded in creating coalitions after elections i.e. come to power; and of which parties the commune elders, mayors and council chairmen came from. To verify the results, we asked the major parties to do the math (Reform Party, soc dems and IRL answered us, Centre Party did not).

Let’s admit: two years before presidential elections, an approach like this is not solid, as coalitions may crumble and commune leaders shift their party affiliations; still, it is one way to measure influence of parties.

And so, across Estonia, Reform Party managed to get into largest number of coalitions. They are in coalitions in 48 communes and 12 cities. Meanwhile, when looking at party membership of city and commune leaders, Reform Party and IRL are quite close.

Reform Party has gotten their people into governing bodies of 51 communes and 8 cities (commune i.e. rural municipality mayor, city mayor, or chairman of council), IRL heads 53 communes and 7 cities. Soc dems, but Centre Party especially, remain far behind. True, should we look at cities alone (as a rule, a city gets more people into electoral body as an average commune), then Centre Party and soc dems come first.

Surely, all such calculations are hypothetical. On basis of these figures alone, it is impossible to tell to what degree a party controls the electoral body. Even so, it is possible to conclude which parties have the upper hand in presidential campaign.

Of course, various concessions have to be made. Firstly: in communes, election coalitions come first, in numbers. True, belonging into an election coalition does not always mean that members thereof have no party preferences.

Let’s take Konguta Commune, Tartu County. Both community mayor and council chairman are IRL members; even so, none run in IRL list, opting for election coalitions (which, for the two, were different). How, in such a case, does one assess the preference of Konguta council representative in electoral body?

Across Estonia, there are dozens and dozens of such confusing political relationships, touching all parties (in this category of party members in power, yet not having run in party’s list, IRL has a clear lead).

As also stated by political commentators: in the electoral body to choose President, composed of Riigikogu members and representatives of local governments, parties have quite a tight reign over their people in Riigikogu and, as a rule, in cities and larger communes. The smaller the commune and the farther away, the harder to predict party power over electoral body members.

Political observers with prior experience in presidential elections say at least 10 per cent of electoral body is a totally unpredictable «swamp», on whom no party can count. Therefore, promises like «if you support my prime minister candidate, then I will support your presidential candidate» are not too convincing, as all will know that the parties are simply not able to control electoral body members as easily as their people in Riigikogu.

Govt parties at slight advantage

Secondly, with electoral body it has to be considered that various local governments get differing numbers of electoral body representatives, due to size of local government. Meaning, for instance: Tallinn sends ten representatives into electoral body. As Tallinn council is controlled by Centre Party, it may be assumed that Tallinn’s representatives will support Centre Party’s presidential candidate.

Other parties also have their monopolies: IRL, for instance, claims they have absolute majority in 15 local governments.

Looking at local elections results and how parties succeeded at forging coalitions, projecting this to the 2016 Presidential elections, we may say that the present coalition parties may shave a slight advantage. Reform Party and IRL do have a lead, with Centre Party close at their heels, and then the soc dems who did improve their results but still are not at power in too many communes.

Whoever wants to «make» president, in two years time, must, like the last time, be able to create a cross-coalition three party alliance. Two would not make it.