A producer of car safety devices, Norma has been making safety belts for over four decades beginning in 1973. Now, a best known industrial enterprise in Estonia, they have focused on details providing greater added value.

A producer of car safety devices, Norma has been making safety belts for over four decades beginning in 1973. Now, a best known industrial enterprise in Estonia, they have focused on details providing greater added value.

Though still assembling safety belts, their share is ever shrinking. In 2010, safety belts sales still amounted to 67 percent of total turnover. Last year, it was down to 35 percent.

As explained by CEO Peep Siimon: when in 2001 they assumed belt production from Autoliv in Sweden, purchasing prices of components were 94 percent of product end sales price.

«We bought for €94 and sold for €100 and the value added in Estonia was six euros. Essentially, this was packaging with cheap labour, warehouse costs and that’s all,» said Mr Siimon.

«Now we have concentrated on a niche with sophisticated technologies, sophisticated products, where the added value would be relatively high. This is not mere assembly and logistics, that something is brought in and taken away. The added value is given here, on location. We bring in metal, make the tools, design these with our own team as part of an international team, and offer our production globally,» he said.

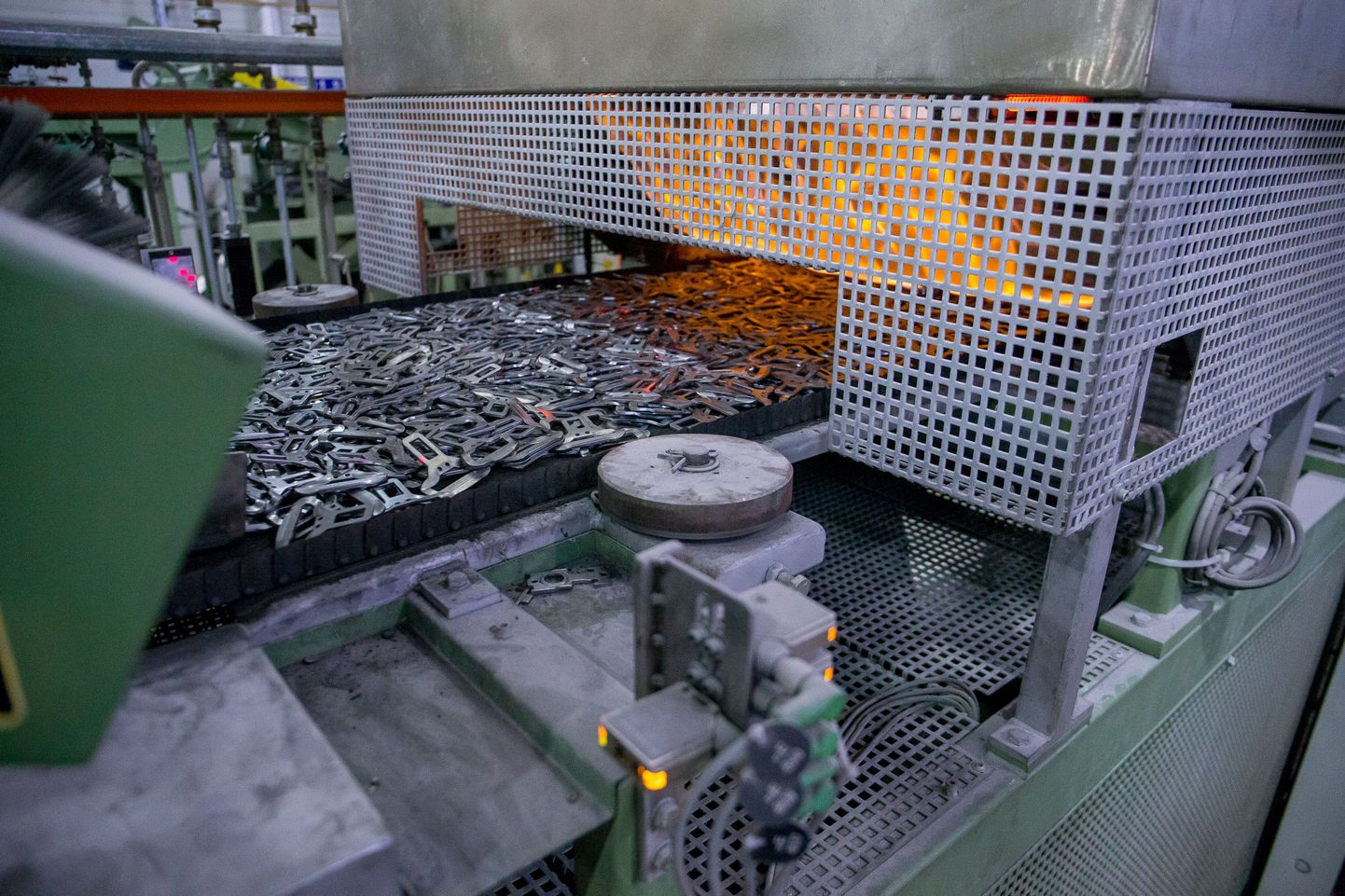

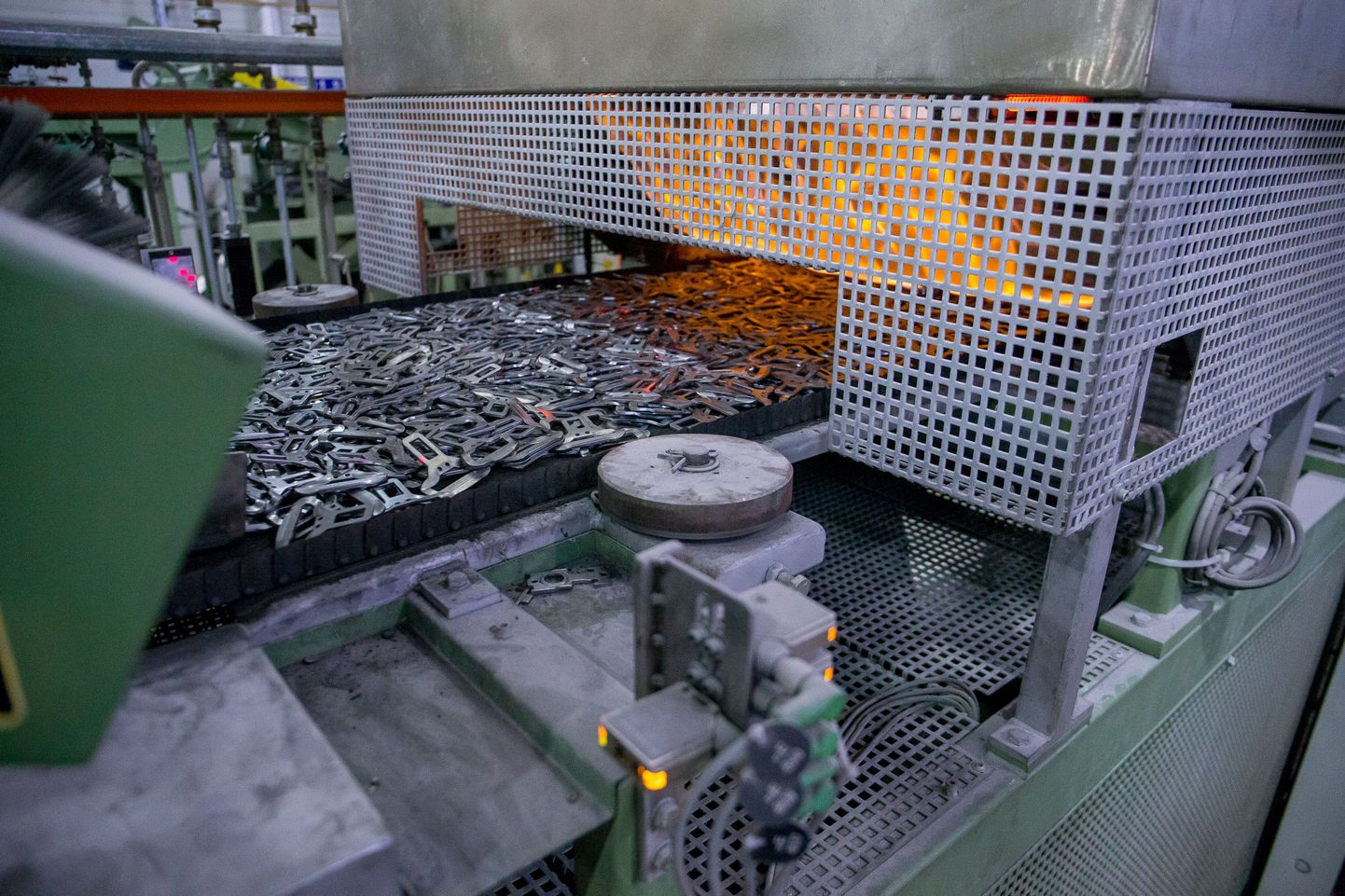

One such product is height regulators for safety belts, a new model of which has just been developed with Germans at Norma. On top of that, they produce precision components at Norma, and buckle-tongues for safety belts.

At Norma, the buckle-tongues are truly a mass production – made 45 million a year i.e. a million a week. The components go to almost all brands from the old customer Lada and Volvo all the way to Bentley.

The Buckle-tongues come in dozens of types, and in varying colours. «From us, they directly go to three main customers, and via them to all cars practically,» explained Peep Siimon.

Considering that about 73 million vehicles are produced globally in a year, and all have an average of five safety belts, this means that every eight vehicle off any plant in the world comes with a buckle-tongue made in Tallinn.

Peep Siimon said that Norma complies with all certificates regarding quality etc. «Car industry is global. If General Motors or Daimler makes a new car, the components must come with same specifications on different continents,» said Mr Siimon.

«We are sending or small components to basically all continents,» he said. The change of strategy and extra added value, however, has not improved the financial results thus far. Both turnover and profits peaked in 2011 and after that the results have declined.

While only in 2013 Norma showed among Estonia’s top hundred largest turnovers, last year and in 2015 this is no longer the case.

«We are down the feeding chain now. While earlier we sold safety belts and bags, now we sell preassembled stuff. The turnover has dropped because when you make tens of millions of bits priced in cents, or if you make hundreds of thousands of belts priced five to 20 euros, that’s where the difference comes from,» explained Mr Siimon.

He said owners are satisfied as Norma is sustainable and competitive. «Alas, not on the belt market any longer,» admitted Mr Siimon.

He said one can only play in the game if a company has development. In a large group, development is concentrated in large hubs – research centres, institutes.

«We do not have that in Estonia. We only have a team which participates in the development phase in certain projects,» said Mr Siimon.

In the segment, competition is tough. Mr Siimon says China has become a major competitor with increased quality and speed of adoption of new products.

«But our products are so specific that few are the players,» said Mr Siimon.

Owner of Norma a global player

Norma is owned by the global maker of vehicle safety equipment Autoliv registered in Delaware, USA and headquartered in Sweden.

The company turned seriously global in 1997 after merger with the US enterprise Morton (as we know by now, it actually took it over).

The products include airbags, safety belts, steering wheels, passive and active safety systems as radars, night cameras and such like.

Last year the group showed $9.2bn in turnover, meaning that Norma yields less than 1 percent of total turnover. Meanwhile, Autoliv makes 143 million safety belts meaning that a third of the group’s safety belts come with buckle-tongues made in Norma.

The group has operations in 28 nations with a total staff of about 60,000. Parts are produced for 100 brands and 1,300 models globally.

Autoliv shares trade at New York and Stockholm stock markets. The company is a good dividends payer and these past five years the shareholders have been paid a steadily growing sum.

Norma ready to pay dividends

Withdrawn from stock market a bit over five years ago, Norma’s share used to be a investor’s favourite as the enterprise paid a stable and diligent dividend and it’s yields were among the best in Tallinn.

True, with lots of free cash on the company’s balance sheet, some shareholders were dissatisfied demanding for more. A leading activist investor was the hedge fund Gild Arbitrage – by now liquidated – which was the only investment corresponding to the name of the fund (arbitrage is seeking ways to earn money from market inefficiencies). Of the other investments of the fund, the Armenian gold prospects were the most (in)famous.

The investors were indignant as, instead of returning the money to shareholders as dividends, Norma preferred to hold it as deposits or lend to parent company.

The controversy with activist investors was solved after Norma was completely taken over and taken of stock market, while recently Eesti Ekspress cited it among companies who avoid income tax.

True, after being delisted, Norma has no longer paid dividends to parent company and at end of last year parent company’s obligations before Norma stood at €24.5m.

Norma chief Peep Siimon says that, for a short while, parent company is paying higher interests on loans than deposits yield in commercial banks.