According to analysts trend won’t stop until Estonian prices catch up with European Union average.

According to analysts trend won’t stop until Estonian prices catch up with European Union average.

Joining the European Union and stepping into euro area has sharply raised prices. Could that have been avoided by staying outside the union?

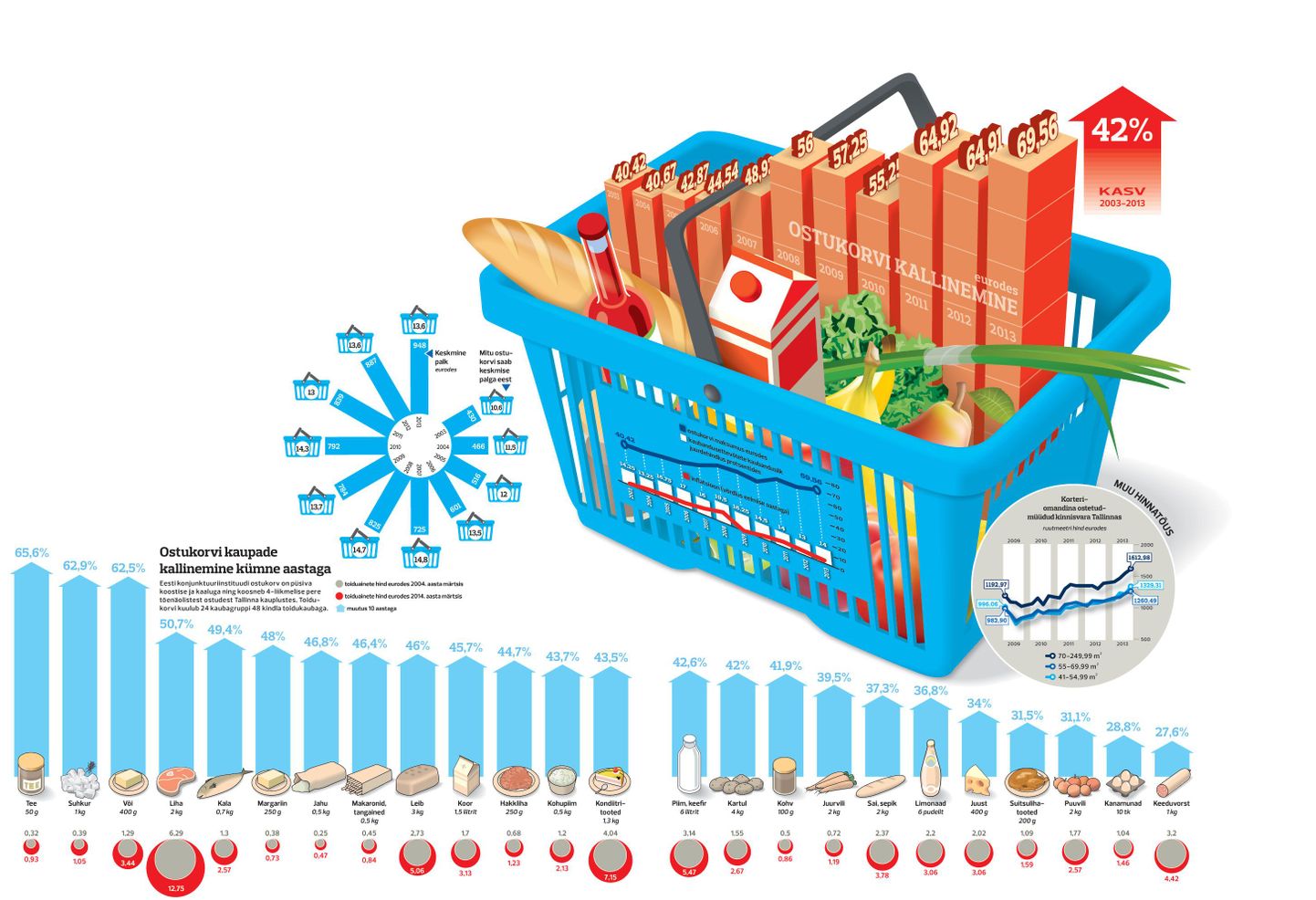

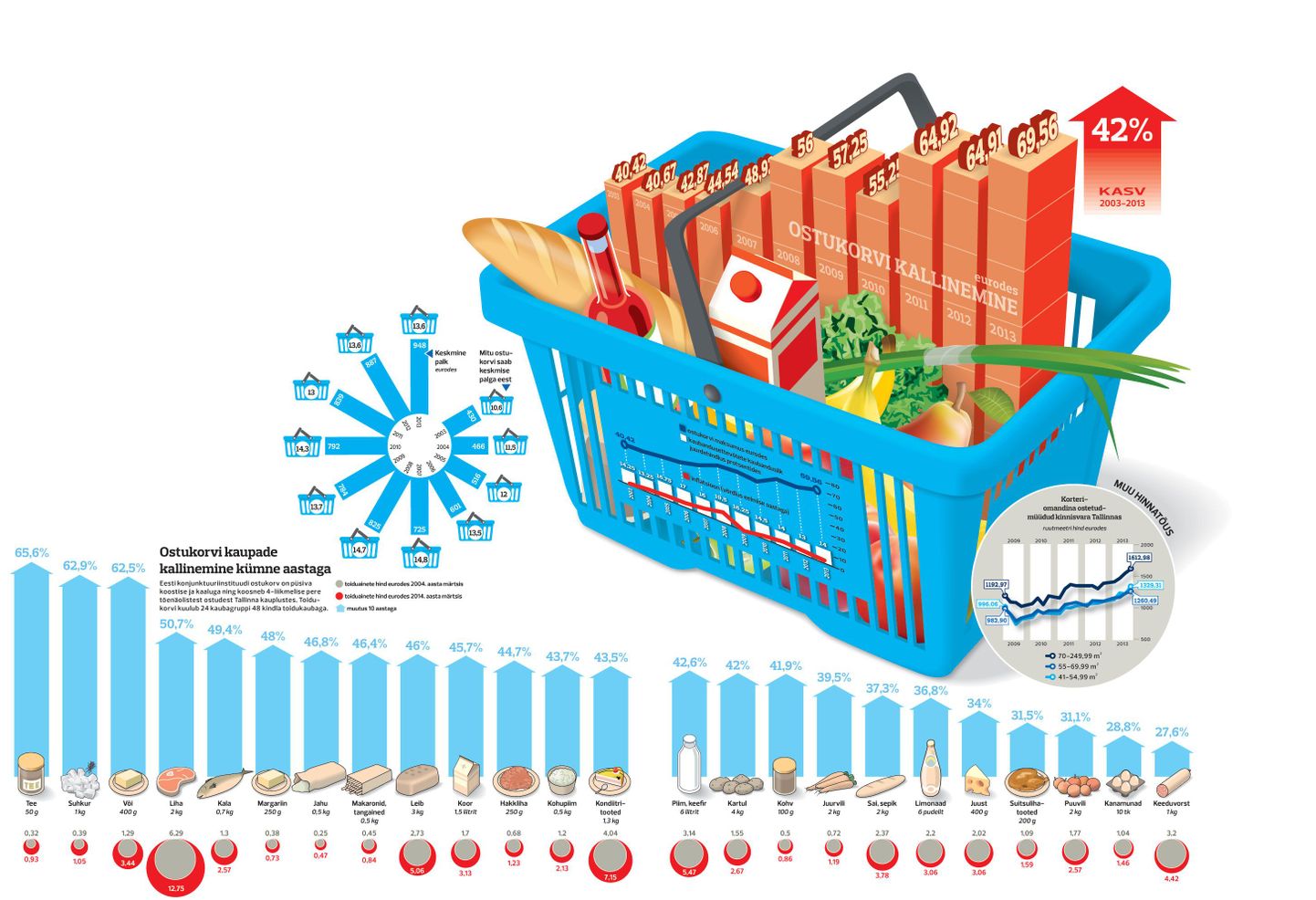

A clear indicator of price rise is the food basket cost complied by Estonian Institute of Economic Research (EKI). According to that, over the past decade Estonia has suffered food product price rise of over 40 percent. The food basket price upward jerk was especially steep after the adoption of euro – close to 15 percent.

«Has price rise been steep? Of course it has,» confirmed SEB private banking strategist Peeter Koppel and brought an example: «Where in the good old days it took 500 kroons, now €50 are easily spent.»

Hard to blame the rise on the greediness of the merchants, as the average mark-up has stayed at the pre-crisis level of about 14 percent – almost unchangeably for the last four years. Over a third of the markup is spent to cover labour costs; another big part takes care of business costs. The merchant keeps a rather meagre percent.

Meanwhile, the rising cost of living isn’t notified by sausage price alone. After the boom, real estate prices are also on a brisk upward march. If in 2009 a square meter of a smaller Tallinn apartment (41–55 m3 – edit) cost about €860, then by last year average price was up at €1,230.

Last Friday, Swedbank Eesti CEO Priit Perens told Äripäev that the average consumer’s ability to obtain real estate has decreased. «In asset price comparison, hidden impoverishment is taking place,» said he.

Finance minister Jürgen Ligi, however, said that prices have risen much less than it seems to people. «People are always too worried about prices – these are not subject to our will, but worrying makes things look worse. Even now, when real inflation is almost nonexistent.»

Next to price rise, it is also important to follow rise of income, and to assess purchasing power. Over the past ten years, average wages have more than doubled. Still, economists differ while assessing real purchasing power of people. Maris Lauri, formerly economist at Swedbank and now adviser to Prime Minister Taavi Rõivas, said on basis of Eurostat data that prosperity has increased: average wages have risen fast as compared to other countries, gross domestic product per capita continues to increase. «People who travel may say that ten years ago they felt poorer while abroad than now,» added Ms Lauri.

The same was claimed by finance minister Mr Ligi: compared to the wages of ten years back, purchasing power is now up over 40 percent. An average salary comparable to today’s average by purchasing power, ten years ago, would have been €693; however, in the final quarter of 2003, average wages amounted only to €455.

Other economists were more subdued when assessing purchasing power of Estonians. Mr Koppel looked to real wages, the dynamics of which – in his estimation – will not point to Estonians doing especially bad. «In context of the crisis, the situation was shocking of course; but otherwise real wages seem to be like the body weight of a middle-aged man – at times it goes up, then down, but mainly up though,» said Mr Koppel. Economist Heido Vitsur says people’s purchasing power has not seen an increase worth mentioning, post crisis.

Mr Vitsur says there are two reasons why it is difficult to say what the direct EU and eurozone effect has been, on the prices. When Estonia joined the EU in 2004, it was followed by a global economic boom. After the switch to the euro, though, the overall recovery from crisis begun.

Still, thinks finance Minister Mr Ligi, while joining the EU people had no fears of price rise – as opposed to when the euro «loomed» – but, in reality, custom fees had an even larger effect on prices back then. According to Eesti Pank calculation, the one-off effect on inflation in Estonia, as it joined the EU, was up to 1.8 percent.

«That assessment also includes the excise rises of the time, regarding which it cannot be said they were necessarily caused by joining the EU,» said Mr Ligi. «But the overall enthusiasm due to joining the EU accelerated economic growth, lending, wage rises and also inflation, till the recent big crisis.»

Mr Vitsur agreed that joining the union was followed by an expectation of wellbeing. At the same time, the economy generally overheated leading to bubbles in non-EU countries as well. As an example of that, Mr Vitsur pointed to Iceland where, not limited to real estate crash, the entire banking system fell apart.

According to economists, it is unavoidable in open economic space that prices and wages even up, and the trend is predicted to continue in this year as well. «The more open the economy, the faster and more intensively this happens. Price rise would have happened even if we had not joined the EU or the eurozone,» generalised Ms Lauri.

------------------------------------------------------

One question: what will happen to prices, this year, and will wages grow?

Peeter Koppel, SEB private banking strategist

The deflationary pressure in the eurozone will probably keep brakes on our inflation; even so, we will maintain an inflationary environment until we have caught up with the euro area. Thus, this year also, we are probably talking about some kind of price rise.

But when it comes to the current wage situation and the developments this year: registered unemployment has dropped relatively low and is almost at the levels of natural local joblessness. Which will mean that in certain sectors employers are quietly buying people over i.e. all who can really do something are highly esteemed. It is important to have more of those who can really do something; and so we come back to investing in people and innovation.

Heido Vitsur, economist

Inflation has slowed in all of Europe, wherefore there is no basis to believe that in the Estonia of slowed-down economic growth price rise would significantly exceed the European average.

Wages, however, have been raised in many places at the start of the year. Estonians have gotten so used to travelling to Finland that the Finnish wage level has made it quite difficult on our labour market. Already, over 60,000 workers from Estonia are listed in Finland; but Estonia has under 600,000 jobs. I think in some sectors the wage rise will continue, in others it will halt and may even go backwards.

Maris Lauri, advisor to Prime Minister, formerly economist at Swedbank

It is estimated that prices will start rising in the second half of the year. Mostly because prices are expected to rise in the world around us.

Regarding wage rise, there are no signs about this slowing down significantly. Statistical Office data should be out soon; but I think in the first quarter of this year wage rise has continued.

Jürgen Ligi, finance minister

During the first months of 2014, price rise was the lowest of the past years in Estonia and eurozone. In Estonia, April price rise was 0.2 percent year-on-year. Mostly, this was due to outside influences, the lowering commodity prices, and the drop of import prices as caused by the strengthening of the euro, as well as the cheapening of electricity.

The decelerating price rise of the second half of last year supports real wage rise, and price rise might accelerate starting this summer: in March and April, consumer prices rose 0.2 percent year-on-year, so for the time being a rapid rise of real wages and real pensions is set to continue for the time being.

In its spring economic forecast, finance ministry expected this year’s inflation to be 1.4 percent and average wage rise to reach 6.2 percent. Thus, people’s purchasing power will continue to improve rapidly.