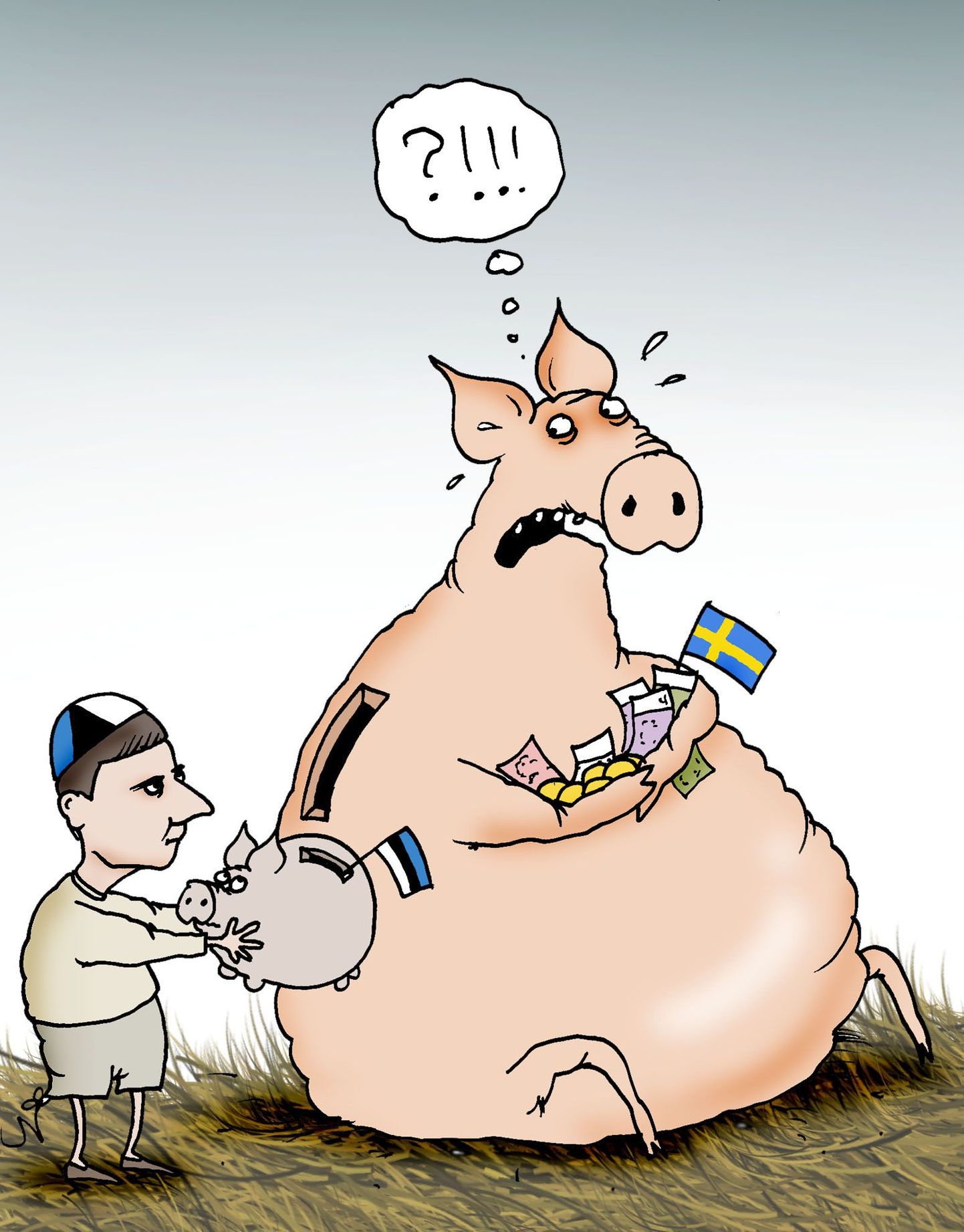

Turns out, however – there is more. As revealed by Tax Board papers, with the past years’ bumper profits, the banks have not paid a cent of corporate tax. Pursuant to local law, enterprises have no such obligation, if they don’t take out dividends. And the banks have been wise enough not to pay dividends. So, in eyes of the law, all is OK. The profit is ever collecting into a closed pond, not a drop trickling into the overall money flow of the state budget.

The problem is nothing new. Far from it: it dates back to the times when enterprises obtained income tax exemption. Which prescribed that in case profits go into investment, the state shall support development of enterprises by not claiming income tax from the sum invested. Should a company, however, pay out the profit, then it undergoes taxation.

Entrepreneurs being no fools, they found a way to get the profit without paying taxes: the profit was loaned to their very selves. The practice was not limited to small companies; even the big and the honourable, some even foreign-owned, did that.

How to solve the problem? Former finance minister Aivar Sõerd found a solution in freewill income tax. The idea is not new, neither is it popular. In 2003, while Reform Party chairman, Siim Kallas suggested that companies spend a tenth of their profit on research and development. Do we need to add, that the idea proved not too popular?